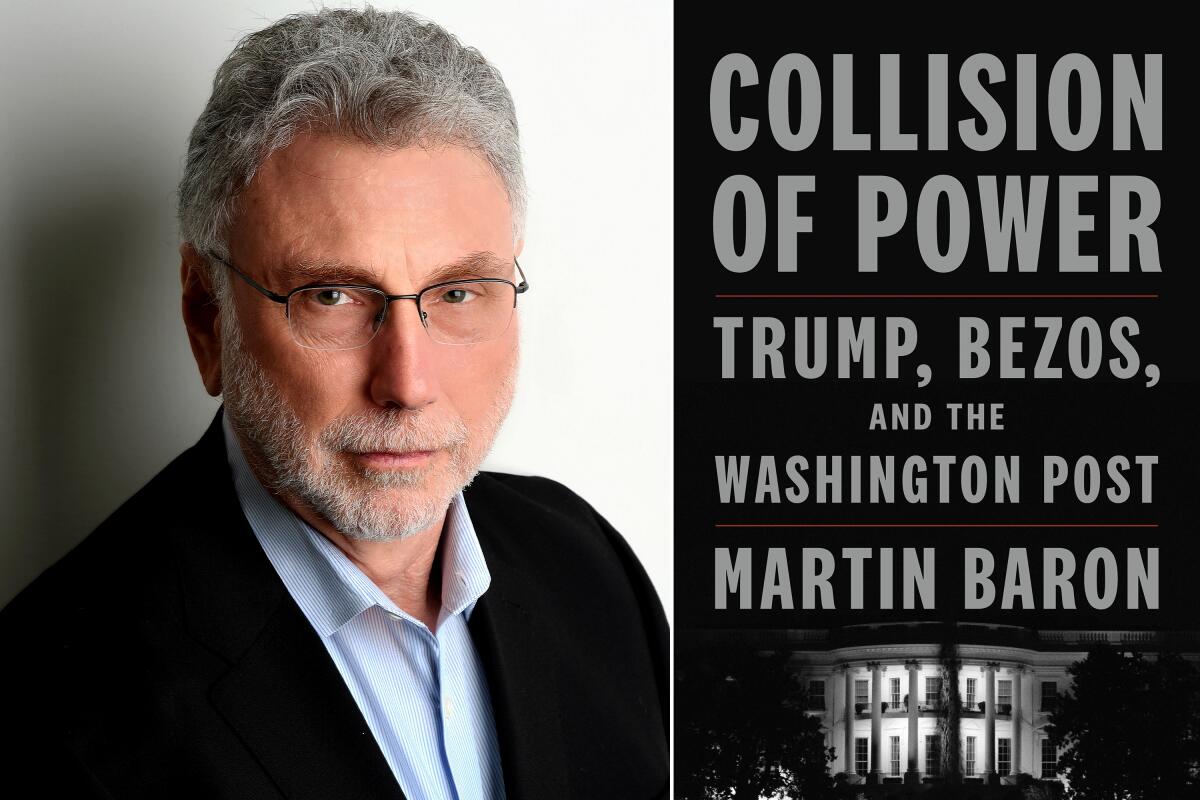

In the 2015 film “Spotlight,” Liev Schreiber played Boston Globe executive editor Martin Baron as “humorless, laconic, and yet resolute.” That is Baron’s own description in “Collision of Power,” a reported memoir about his more recent gig as executive editor of the Washington Post.

Baron has no beef with the movie’s portrayal of his leadership of the Globe’s Pulitzer Prize-winning investigation of sexual abuse in the Catholic Church. What does irk him is that his reputation didn’t deter critics from slamming his cautious handling of sexual harassment and assault stories at the Post. “That stung,” he writes.

Amid intense economic pressures and yawning generational, political and cultural divides, life at the apex of the newspaper hierarchy can be nasty, brutish and short. Baron, an avatar of traditional journalistic values, has weathered the challenges better than most. A veteran of both the New York Times and the Los Angeles Times, he led three newsrooms (the first was the Miami Herald) to multiple awards and left each on his own terms.

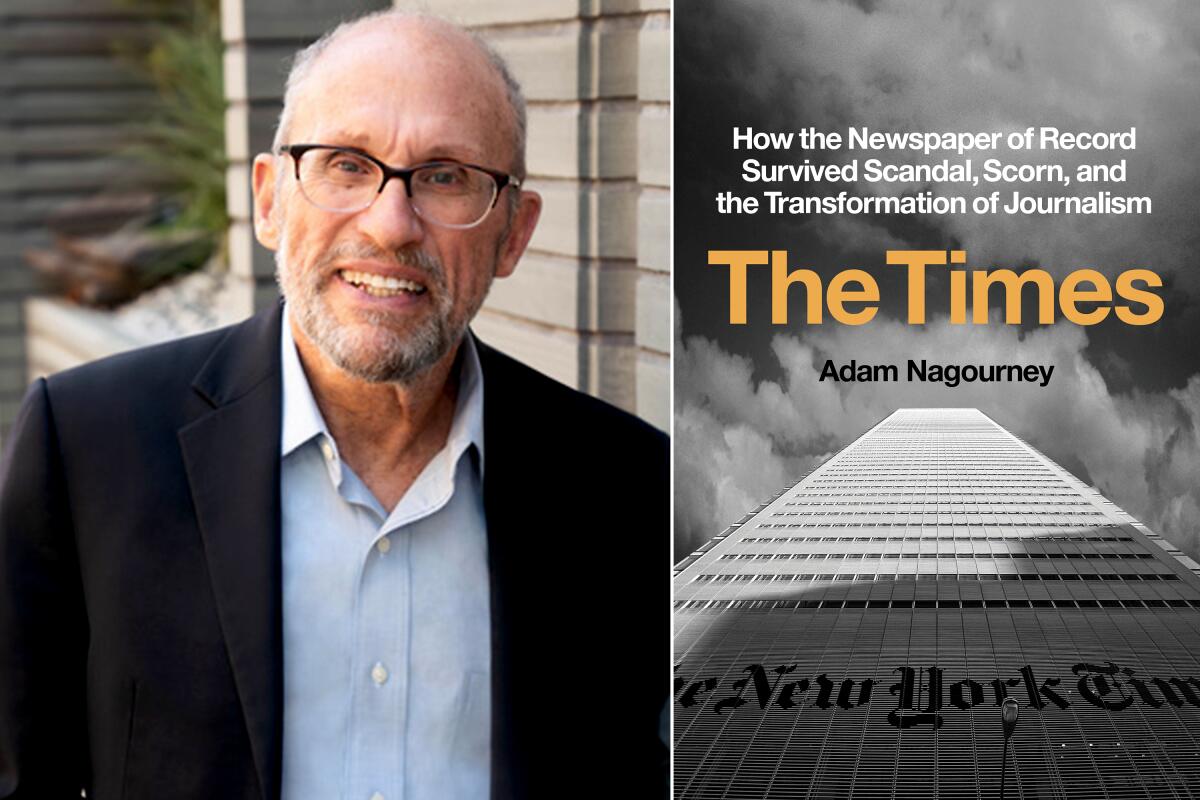

The same can’t be said of several recent top editors of the New York Times, hobbled variously by nettlesome personalities, bad timing and worse luck. Adam Nagourney’s “The Times,” an often enthralling chronicle of four decades (1976-2016) of management upheaval and digital transformation, delivers the gossipy goods, thanks in part to interviews with nearly all the surviving principals. Nagourney’s insider status — he still works for the Times, covering West Coast cultural affairs — no doubt contributed to his access.

Media junkies will find both books indispensable. But like Robert Caro’s biographies, they should appeal to anyone interested in power: how it operates, and how it is lost. The context here is the continuing struggle to keep the news industry solvent, an exhausting pursuit even for the most gifted and resource-rich organizations.

Both volumes offer a version of Great Man (and in the case of the Times, one not-so-Great Woman) history. Neither dwells on the legions of reporters and editors whose careers have been derailed as the business, fixated on declining profits and slow to adapt to the internet, has shed jobs. What the books do show is how these two major news organizations managed to pivot to life-sustaining digital subscriptions while much of the local news landscape lay in ruins.

Former Washington Post executive editor Martin Baron is out with a new reported memoir on the institution, “Collision of Power.”

(Essdras M. Suarez; Flatiron)

“Collision of Power” details clashes between the Post and President Donald Trump and between Trump and Jeff Bezos, the multibillionaire founder of Amazon. Bezos scooped up the struggling Post from the Graham family for $250 million in 2013, just months after Baron became executive editor.

Baron repeatedly underlines Bezos’ respect for the Post’s journalistic independence. The newspaper covered Amazon’s business dealings and the tabloid-worthy dissolution of Bezos’ marriage without interference from the boss. Meanwhile, Bezos poured money — within limits — into new hires, upgraded the Post’s technology and, despite threats to his business, ignored Trump’s demands that he curb the Post’s investigative zeal. When his editors were stymied, Bezos himself picked the paper’s new slogan: “Democracy Dies in Darkness.”

Baron finds Bezos charming. He does complain mildly that the owner could have spent more time with Post staff — and, more substantively, that Bezos didn’t fully understand the value of editors.

To Post readers, Baron’s recaps of Pulitzer Prize-winning coverage of the Trump administration and the January 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol, as well as other investigative coups, will be familiar fare. He does break some news of office strife, reporting that the political staff was more gung-ho about stories on ties between the Trump campaign and Russia than the national security team and Moscow bureau — a divide about which, “stunningly,” he himself wasn’t initially informed.

“Collision of Power” tells us little about Baron’s life and career prior to the Post. Nevertheless, the book is revealing of the man.

In the wake of Black Lives Matter, #MeToo and the police murder of George Floyd, Baron slogged, sometimes ungracefully, through conflicts with his staff over diversity, political participation and the use of social media. Two of Baron’s biggest headaches were the Pulitzer Prize-winning Black reporter Wesley Lowery and Felicia Sonmez, a reporter who identified as a sexual assault survivor. In Baron’s telling, neither cared much for his treasured norm of journalistic objectivity. Both would eventually leave the Post.

Baron declares himself “weary of well-meaning but moralistic young journalists — and their forever enabling union — lecturing me on best management practices when precious few had ever managed anyone” or “had any appreciation for the difficult task of meeting ambitious growth goals that bestowed benefits on all of them.”

“Nothing was more hurtful,” he adds, than “the invective leveled against me by colleagues — whose skill and bravery I admired and whose news organization I had busted my butt for eight years to turn around.”

Beneath his vaunted cool, Baron was feeling unappreciated and misunderstood. By the time he retires, in February 2021, it seems he can’t wait to leave.

Adam Nagourney is the author of a chronicle of the recent history of the New York Times, “The Times.”

(Kyle Froman; Crown)

By contrast, as Nagourney recounts, New York Times executive editors, starting with the legendary A.M. Rosenthal — “self-assured to the point of arrogance” and later “embattled and self-pitying” — often had to be pried out of their jobs. Rosenthal, in fact, had to be pried out twice — the second time, in 1999, from a 13-year tenure as an Op-Ed columnist.

The Times has spawned numerous fine histories and memoirs, including Gay Talese’s “The Kingdom and the Power” (1969), Susan E. Tifft and Alex S. Jones’s “The Trust” (1999) and former managing editor Arthur Gelb’s “City Room” (2003). Nagourney’s volume, both candid and fair-minded, is a valuable addition to the canon, adding detail to already well-reported stories.

Nagourney analogizes two abrasive and rivalrous figures, Howell Raines and Jill Abramson. Raines, who presided over the newsroom from 2001 to 2003, frequently tangled with Abramson, then Washington bureau chief. Both, says Nagourney, “were calculating and ruthless when they needed to be and capable of the rawest candor — characteristics that would help lift them to the top of the newsroom.” Their hubris would also contribute to their demise.

Raines was felled, in large part, by the plagiarism and fraud perpetrated by a troubled young reporter, Jayson Blair. A lesser embarrassment, involving a correspondent relying too heavily on freelance reporting, contributed, as did the widespread staff antagonism Raines had aroused. In the end, Nagourney writes, “he did not see the kindling piling up around his feet.”

Abramson, the Times’ first female executive editor, won the job despite foreign editor Susan Chira’s warning to publisher Arthur Sulzberger Jr. that her management style was “volatile, sporadically cruel, intolerant of dissent.” As executive editor from 2011 to 2014, Abramson fought what she saw as business incursions into the newsroom and fatally alienated her managing editor and onetime friend, Dean Baquet. After her firing, Baquet (who had briefly served as the L.A. Times’ executive editor) would become the New York Times’ first Black executive editor.

Interwoven with these juicy, neo-Shakespearean tales is Nagourney’s account of the Times’ digital pivot, “a messy and occasionally embarrassing exercise that had sometimes seemed destined for failure.” The Times’ 2011 implementation of a paywall was copied successfully by the Washington Post, less so by other newspapers around the country. (And even the Post, since Baron’s departure, has been flailing financially, according to reporting in the New York Times.) This complex story — of just-in-time transformation and its national fallout — likely merits a book of its own.

Klein, a cultural reporter and critic in Philadelphia, was a longtime reporter and editor at the Philadelphia Inquirer and a contributing editor at the Columbia Journalism Review.