WASHINGTON — Former President Donald Trump has been out of office for more than three years but he just notched a big win at the Supreme Court.

Friday’s ruling that overturned an important 1984 ruling called Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council was a belated victory for Trump’s deregulatory agenda, with all three of his appointees to the high court joining the 6-3 conservative majority.

“The decision was the culmination of a decade-long, billionaire-funded campaign to capture and weaponize the unelected power of the Supreme Court to deliver huge windfalls for corporate interests at the expense of everyday Americans,” said Alex Aronson, a former Democratic staffer in Congress who is executive director of Court Accountability, a judicial oversight group.

During the Trump administration, the Republican-led Senate, which had the job of confirming the president’s judicial nominees, “became a conveyor belt for ideological, corporatist judges,” he added.

Business groups hailed the ruling, with the National Federation of Independent Business saying on Friday that it will “level the playing field in court cases between small businesses and administrative agencies.”

Overturning Chevron, a ruling that business interests long disliked, has long been a goal of conservative lawyers, who saw it as giving bureaucrats too much power.

The original decision said courts should defer to federal agencies in interpreting laws that were ambiguous, but in Friday’s ruling, Chief Justice John Roberts said that approach was “fundamentally misguided.”

“Perhaps most fundamentally, Chevron’s presumption is misguided because agencies have no special competence in resolving statutory ambiguities. Courts do,” he added.

Don McGahn, Trump’s White House Counsel, memorably said in 2018 at a conservative political conference that the president’s judicial selections and the attempt to roll back regulations “are really the flip side of the same coin.”

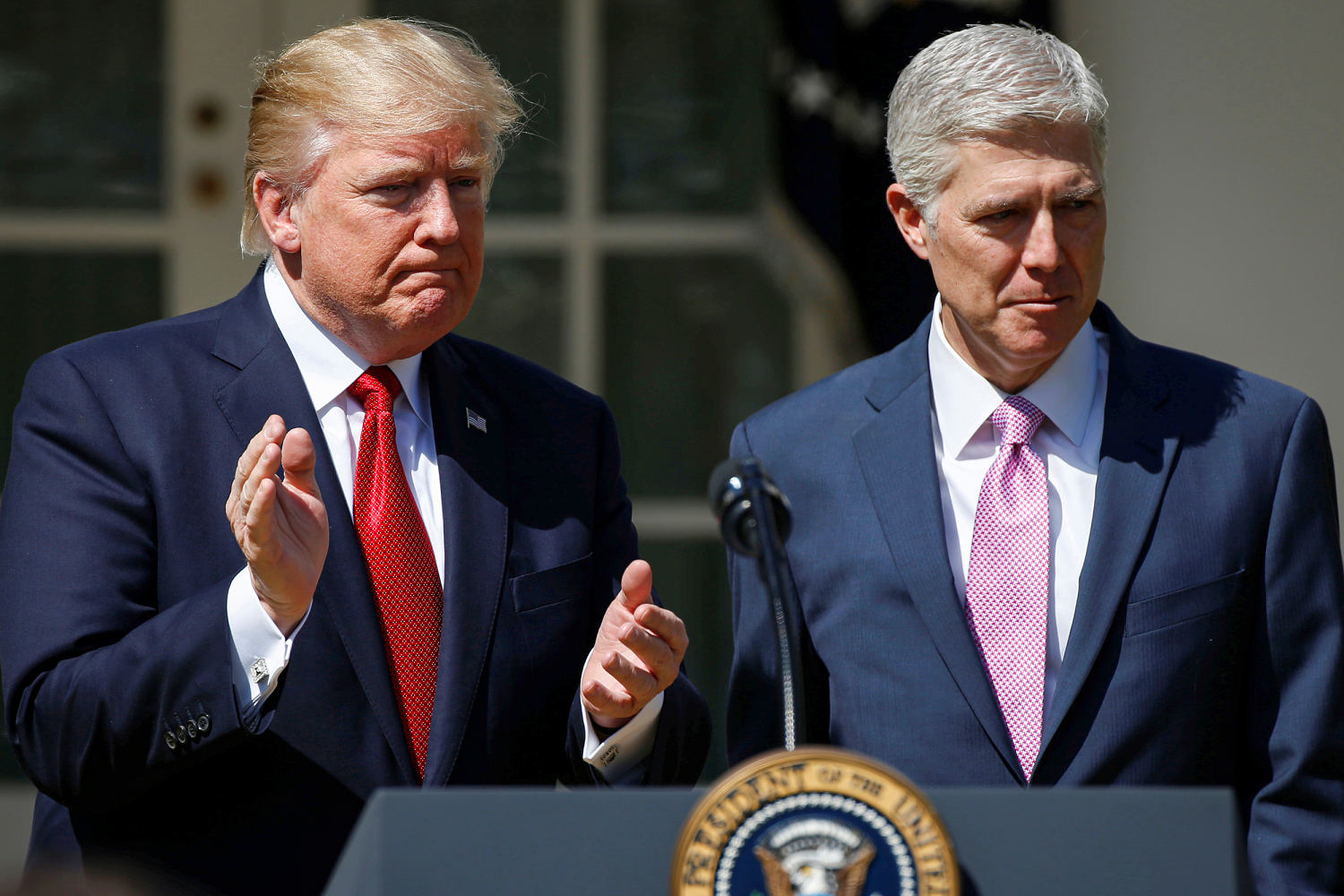

He cited Justice Neil Gorsuch, who had just been appointed at the time, as an example of what the administration was looking for in nominees. One of the reasons Gorsuch appealed to McGahn and others who had a say in his nomination in 2017 was that he had written a scathing opinion suggesting Chevron should be overturned.

Gorsuch duly signed on to Robert’s majority opinion on Friday, as did fellow Trump appointees Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett.

McGahn, who is now back in private practice with the Jones Day law firm, did not respond to a request seeking comment about Friday’s ruling. The Trump campaign did not respond either.

On another deregulatory issue, the Supreme Court in the coming days could act on a petition filed by McGahn and his Jones Day colleagues that seeks to gut the power of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration to set workplace safety rules.

Sean Donahue, a lawyer who often represents environmental groups, said that overturning Chevron became “a kind of litmus test” on the right for selecting judges along with hostility to abortion rights ruling Roe v. Wade, which the Supreme Court overturned two years ago.

One criticism of the latest ruling — echoed by liberal Justice Elena Kagan in her dissenting opinion — is that the court is seizing power for itself from federal agencies.

“A rule of judicial humility gives way to a rule of judicial hubris. In recent years, this court has too often taken for itself decision-making authority Congress assigned to agencies,” Kagan wrote.

Democratic members of Congress also weighed in, with Sen. Richard Blumenthal, D-Conn., describing the ruling as “prioritizing corporate greed over the health, safety, and welfare of the American people.”

The ruling came a day after the court in another 6-3 decision on ideological lines had weakened the power of the Securities and Exchange Commission, prompting an equally vigorous dissent from liberal Justice Sonia Sotomayor.

The fear among those on the left is that the Chevron ruling will handcuff agencies from tackling major issues like climate change because judges will constantly second-guess their expertise.

Whether the ruling will have such a broad impact remains to be seen, with some commentators saying that in most cases judges will still give close attention to what agency experts say.

Thomas Berry, a scholar at the libertarian Cato Institute, said the ruling correctly ended a doctrine that gave too much power to agencies to judge the scope of their own power.

“Contrary to the dissenters’ view, overruling Chevron will not give judges a newfound power to decide questions of policy,” he added.